This eulogy honors the lives of Lorenzo Orsetti and Ahmed Hebeb, who were killed during the last days of the fighting against the Islamic State in March 2019. For more background on the conflict, read this article and this interview with Tekoşîna Anarşîst.

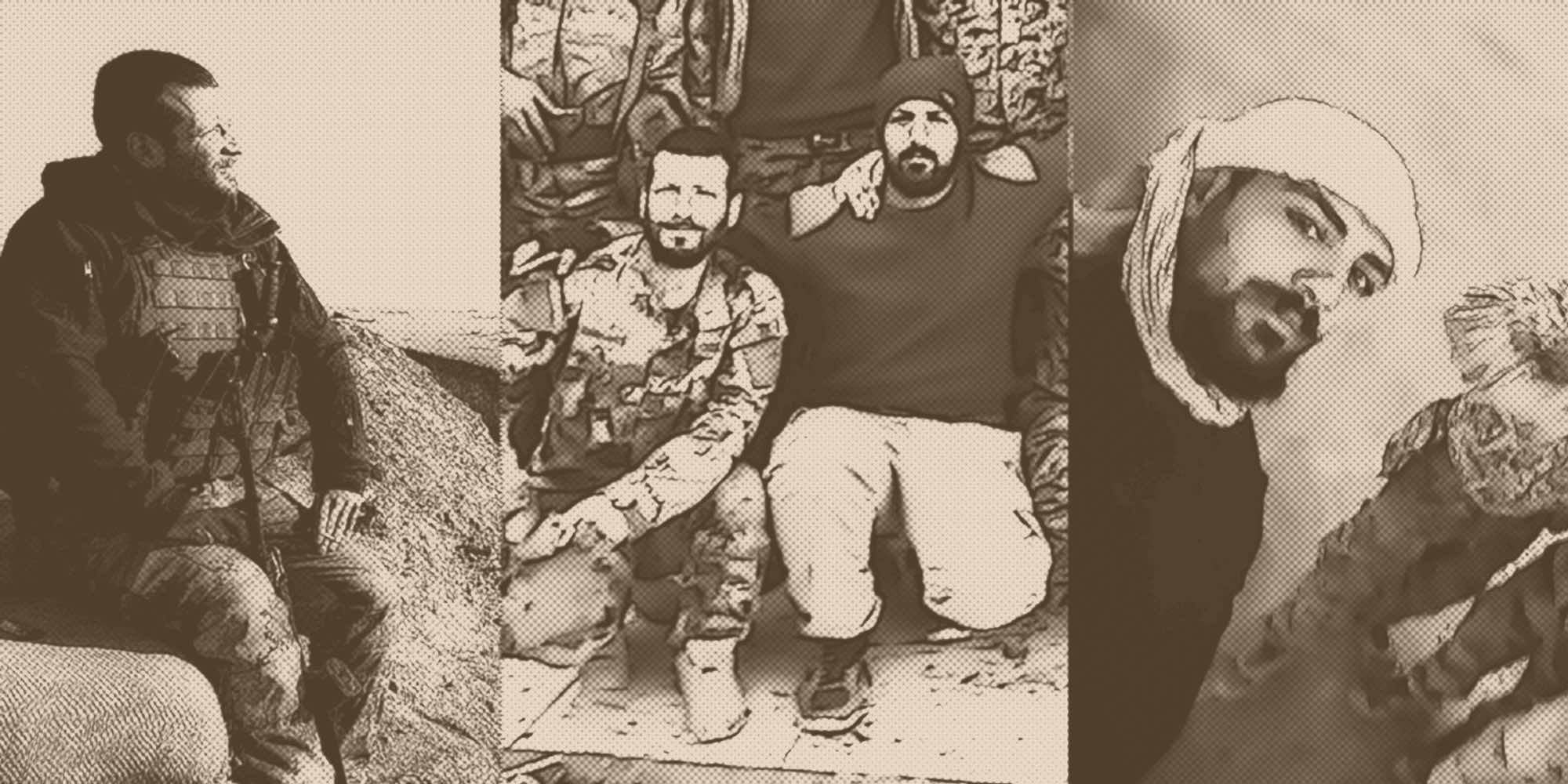

Lorenzo Orsetti and Ahmed Hebeb in the vicinity of Baghuz in March 2019; the last known photograph of either of them.

Lorenzo Orsetti

Three years ago, on March 18, 2019, my friend Lorenzo Orsetti was killed in action during the battle of Baghuz Fawqani. He was fighting with the Syrian Democratic Forces against the last bastion of the Islamic State in Syria. Before any more time passes, I would like to say a few words in his memory.

Lorenzo was an anarchist from Florence, Italy. At the time of his death, he and I were members of Tekoşîna Anarşîst, a group of anarchist internationals participating in the ongoing revolution in northeastern Syria, otherwise known as Rojava.

I met Lorenzo on my first day in Syria and I was with him nearly every day of the last six months of his life. Until he died, I never knew his real name, nor where exactly he was from. To me, he was Tekoşer Piling—that was his nom de guerre. It means “Struggle Tiger” in Kurmanji Kurdish.

In some ways, Lorenzo and I knew very little about each other. In all the time we spent together, we rarely discussed our feelings, the future, or our past lives back home. Nevertheless, we were comrades in arms. We served in the same unit, slept in the same room, trained and exercised together every morning, alternated shifts on guard duty every night, shared hundreds of meals and thousands of cups of tea, rotated chores, cleaned up after each other, and deployed to the front line together twice, where we survived several firefights and various close brushes with death. I trusted Lorenzo with my life, and he never let me down.

Lorenzo Orsetti with the flag of Tekoşîna Anarşîst. “In this picture, he was being self-deprecating by being as over the top as possible.”

What can I say to do justice to Heval Tekoşer?

First and foremost, I will say that Lorenzo was a revolutionary in action and conviction, and that he was very brave. He did not come to Rojava to make money, to live off of the largesse of the movement, or to get famous on the internet. He took his duty as an internationalist seriously. For the year and a half that he served in Syria, he volunteered for every single assignment possible, from Afrin to Deir Ezzor, from one end of the liberated territory to the other. At various times and places, he fought with the predominately Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG), the Turkish communist organization TIKKO, Arab units of the Syrian Democratic Forces, Anti-Fascist Forces in Afrin, and Tekoşîna Anarşîst. He wasn’t messing around. By the time he died, he was a seasoned and widely respected veteran, well known as the first in the line of fire and the last to leave. I had begun to believe that Lorenzo was bulletproof—until he wasn’t.

That said, Lorenzo was by no means a one-dimensional soldier of fortune. He did not love war for its own sake. He read and wrote constantly. He studied history, politics, language, theory, tactics and strategy. His Kurmanji was decent and he was learning Arabic. He knew what he was fighting for, and he truly believed in the principles of autonomy, ecology, and women’s liberation that we saw being put into practice in Rojava, however imperfectly. He lived by his principles and he died for them.

Lorenzo Orsetti at the front in the desert outside of Hajjin in Deir Ezzor at the end of 2018.

In addition to his considerable prowess as a freedom fighter, Lorenzo was an all-around remarkable human being. A chef by trade, he would regularly conjure up delicious meals from basic rations. On birthdays and special occasions, he would track down better ingredients and spend hours making gnocchi and delectable sauces from scratch. He spoke English well, if not exactly fluently, peppering it with fabulous malapropisms, Italian idioms, and peculiar turns of phrase. He could get his point across in a meeting with brutal precision, using half as many words as a native English speaker would. He was quick to anger and quick to forgive, capable of firing off a volley of hair-raising insults when provoked and of completely forgetting the incident within minutes. Lorenzo loved dogs and was especially kind to puppies. He had a thing for odd techno, jihadi nasheeds, and the song “Live By The Gun” by Waka Flocka Flame. He was short and stocky, covered in tattoos, and a ranked world-class master of the video game “Warhammer 40,000: Dawn of War III.” If there was ever a moment where there was nothing more important that he had to do, he could be quite content to wrap himself up in a blanket, stretch out on the floor, break out his phone, and do battle with the orks of Tartarus, a practice that—for reasons quite beyond me—he would refer to as “pumping my cannon.” He was a real one.

Lorenzo Orsetti in Rojava in 2018.

A lot of my most vivid memories of Lorenzo, and of Rojava in general, revolve around sleep and the lack thereof.1 In my mind, he is the tiny glowing ember of a cigarette emerging out of the darkness, long awaited, coming to relieve me of my position and to tell me that I can finally rest. Şev baş, heval.

Lorenzo was killed on March 18, 2019, on the last day of the last battle of the last major engagement of the territorial war against the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria. I had just returned from the front at Baghuz Fawqani. He left for the front there the night I got back from it. We said serkeftin, embraced, and that was that. Within a few days, Baghuz had fallen and Lorenzo was a legend and a martyr.

Lorenzo Orsetti with the red and black anarchist flag.

Three years have passed now. I go about my life in obscurity, surrounded by my loved ones. I wish that Lorenzo had made it home from Syria, as I did. I wish that I had his number in my phone and that I could hear his voice again. Nonetheless, I do believe that there are things in this life that are worth dying for. From the perspective of the civil society of Rojava, I do not think that there was anything to be done about ISIS except to defeat them by military means. Somebody had to do it. Lorenzo did his part.2

To his loved ones in Florence, I would like to say that I too cared for Lorenzo in my way. As my friends and I said in our first statement following his death: “A part of us died with him, and a part of him lives on with us.” We hope that you are proud of him, and that you can understand the choices that he made. I will leave the reader with Lorenzo’s last words, translated for posterity by his friends gathered around a bare table somewhere in northern Syria on March 18, 2019. Rest well, heval.

Lorenzo Orsetti in January 2019: “Just after we returned from the front in Deir Ezzor.”

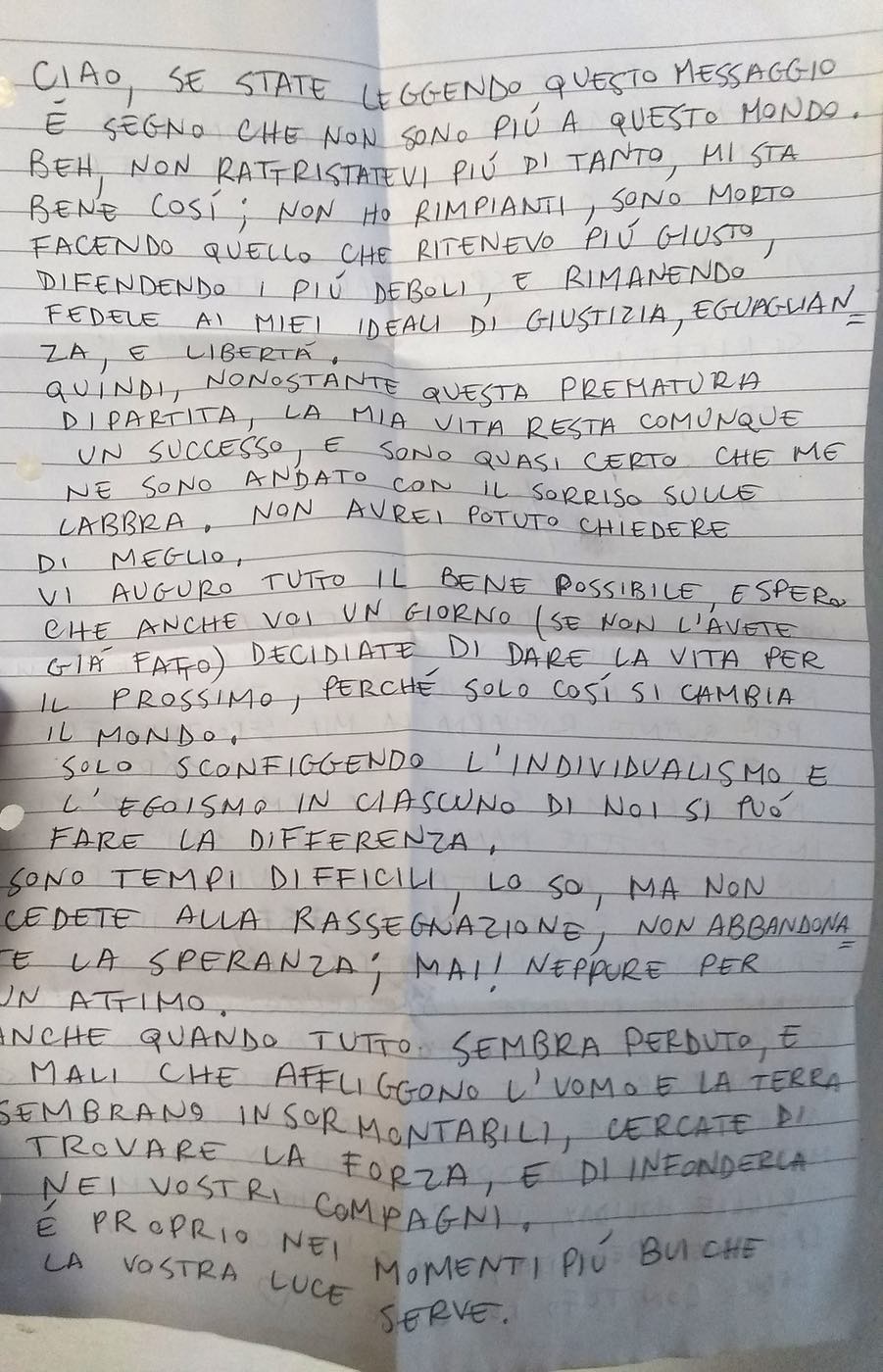

Hello.

If you are reading this message, then it means that I am no longer of this world. Don’t be too sad, though, I’m OK with it; I don’t have any regrets and I died doing what I thought was right, defending the weak and staying true to my ideals of justice, equality, and liberty.

So in spite of my premature departure, my life has been a success, and I’m almost certain that I went with a smile on my face. I couldn’t have asked for more.

I wish all of you all the best in the world and I hope that one day, you too will decide to give your life for others (if you haven’t already) because that is the only way to change the world.

Only by combatting the individualism and egoism in each of us can we make a difference. These are difficult times, I know, but don’t give in to despair, don’t ever abandon hope, never! Not even for a second.

Even when all seems lost, when the evils that plague the earth and humanity seem insurmountable, you must find strength, you must inspire strength in your comrades.

It is in the darkest moments that we have greatest need of your light.

And remember always that “every storm begins with a single raindrop.” You must be that raindrop.

I love you all, I hope you will treasure these words for time to come.

Serkeftin!

Ⓐ︎

Orso,

Tekoşer,

Lorenzo.”

Tekoşer’s şehid letter. Every fighter in Rojava writes a letter like this for release in the event that they do not make it home.

“And remember always that ‘every storm begins with a single raindrop.’ You must be that raindrop. I love you all, I hope you will treasure these words for time to come.”

Ahmed Hebeb

Lorenzo Orsetti fell in battle side by side with an Arab fighter named Ahmed Hebeb. Those of us from Tekoşîna Anarşîst knew him as Rafiq Şamî. It was not a coincidence that they were together that day. Lorenzo and Ahmed knew each other well from Lorenzo’s previous four rotations to Deir Ezzor. During one of these occasions, Ahmed stripped down to his boxers, counting out for us from head to toe twenty-seven separate wounds that he had received while fighting ISIS over the years. Lorenzo wanted to be where the action was, and Ahmed always knew where to find it. They died together, in a hail of bullets with both guns blazing, providing covering fire to a group of their comrades who were retreating in the face of a desperate ISIS counter-attack. Ahmed was beheaded. For whatever reason, Lorenzo was not.

At Ahmed’s şehid ceremony, my friends and I helped carry his casket. His friends and family were at first confused as to why a group of foreigners had materialized at their loved one’s memorial. My Arabic is atrocious, but I pulled up pictures on my phone of Ahmed, Lorenzo, and I together in the desert of Deir Ezzor. “Şamî!” I said. “Tekoşer! Heval! Rafiq! Şehid!”

The revolution in Rojava and the war against ISIS in that part of the world have often been portrayed in the West in Orientalist and Islamophobic terms—especially by reactionaries, but also by some leftists and anarchists. Kurdish people have been fetishized and romanticized—they are portrayed as a bloc, as “the only sane people over there,” while Arabic people are dehumanized and portrayed as crazed terrorist sympathizers.3 This is especially galling to me because—while I cannot speak for other times and places during the war—the reality of what I saw in Deir Ezzor in the winter of 2018 to 2019 was that the overwhelming majority of the soldiers doing the worst of the suffering and dying to wipe ISIS off of the map were Sunni Arabs like Ahmed. Bigots and fools can say what they will about Arabs and people from Islamic societies in general, but what I saw was that when some of the most malicious jihadis in the entire world converged on northeastern Syria to pursue a program of rape and genocide, a great many Sunni Arabs including Ahmed Hebeb took up arms to stop them.

Ahmed Hebeb and Lorenzo Orsetti at the front outside of Hajjin in Deir Ezzor, December 2018.

Ahmed gave his life engaged in combat with people who war had turned mad, people who had chosen to make themselves into enemies of humanity at large. Many of these people were Ahmed’s own countrymen, people who spoke the same language and worshipped the same God. Today, the conditions that sent Syria spinning into war appear to be generalizing across the entire world. The defenders of the neoliberal status quo are showing themselves to be bereft of both vision and answers. As those of us in the so-called West reckon with our own versions of ISIS in this age of ascendant ethno-nationalism, only time will tell how many people of good conscience in Christian societies will be ready to do as Rafiq Şamî did.

On behalf of Tekoşîna Anarşîst, I would like to say to Ahmed and the countless Middle Eastern men and women like him: we have not forgotten you nor the lessons that you taught us.

In the spirit of Ahmed and Lorenzo,

An anarchist.

Ahmed Hebeb and Lorenzo Orsetti at the front in Deir Ezzor, in the vicinity of Baghuz, March 2019, not long before their deaths.

-

Lorenzo had to be woken up in a very particular way, a process that I eventually came to master. You see, some comrades will trick you when it comes time to wake them for guard duty, especially when they have been coping with chronic sleep deprivation for months. They will sit up and have a whole conversation with you. But they are not truly awake. As soon as you leave them, they will lie back down and fall asleep, extending your watch indefinitely and eating into your priceless sleep time. So you must insist, you must prod them until they are standing, until they are fully geared up, until they are actually walking with you in the direction of their post. Woe betide the person who attempted to wake up Lorenzo in this way.

Quite the opposite, as soon as you spoke a single word to Lorenzo, he would be fully awake. He would not move a muscle, but he would grunt one time. With this grunt, you could be certain that he would be at his post precisely ten minutes later, without fail. However, it was vitally important to him that he have this ten minutes to lie perfectly still, smoking a cigarette in silence and acclimating his mind to the horrible fact that he was not only awake but that he was going to have to get up. As I would come to learn, if you made the mistake of prodding him any further during this time, you would soon find yourself face to face with an enraged and frightfully profane Italian.

And yet, at any time of day or night, whenever anything legitimately alarming would happen, such as incoming fire, weird lights, the whir of a drone, or unvouched-for explosions, he could wake up out of a dead sleep and get into position with the speed of a cheetah. You could count on it. ↩

-

This does not mean that the military defeat of ISIS in Iraq and Syria has resolved any of the issues that gave birth to ISIS in the first place. It has not. Abdullah Öcalan himself once wrote that “military victories cannot bring freedom; they bring slavery.” In my observation, he was correct. ↩

-

In fact, the revolution in Rojava is not an ethno-nationalist project, but an ideological one, as practically everyone involved in the Kurdish liberation movement that I personally know there would agree. None of the ethnic or religious groups are monolithic. There are Kurds who bitterly oppose the movement and Arabs, Assyrians, Armenians, Turks, and others who participate in it. ↩