Since 2001, the collectively-run website Antijob.net has provided a “blacklist of employers,” offering a space for laborers in Russia to report on their negative experiences at work. As Russian media and labor organizing have come under increasing pressure, Antijob continues to provide a crucial resource for ordinary employees, even in an extremely repressive environment. Russian corporations and government agencies have repeatedly attempted to bribe the publishers or suppress the site, without success. The so-called “Great Resignation” and a popular Antiwork Reddit site have recently made waves in the United States; we conducted the following interview with Antijob to learn what anti-work agitation looks like in Russia.

Antijob has also played a role in supporting protests against the invasion of Ukraine, informing Russian workers of their legal rights on the job if they arrested while protesting.

As appendixes, we’ve included the Antijob manifesto, the Antijob statement against the invasion of Ukraine, and some examples of the reports workers publish on the site.

“Remember and tell others: your interests are opposed to the interests of the employer. This is a struggle that has been going on for centuries. The struggle between those who are trying to make a living and those who want to buy a new yacht.”

-Antijob, “No loyalty to the employer!”

Employers always write about Antijob. They say this and that—they slander, they claim that they were slandered, they talk about the intrigues of their competitors. Come on, they say, remove the story about the next LLC “Lepyoshki and Matryoshki,” otherwise we will sue you. Or, on the contrary, they offer money for us to remove the material…

To be honest, we don’t really want to make employers better. Conflict between employers and workers, whether acute or dormant, is an integral part of capitalism. It will be fully overcome only with the rejection of the wage labor system as such.

-Antijob, “The presumption of class guilt”

“No loyalty to the employer!”

First, explain what Antijob.net is and what it does.

Technically, we are a feedback web page where workers can leave negative feedback about their jobs. Also, we are a micro-media platform about work and labor.

Politically, we are an anarchist project highlighting the problem of wage labor, calling for workers to organize to fight for better working conditions and, of course, against capital and the state.

What inspires you to maintain Antijob?

Probably the main reason for the continuation of the project and its constant regeneration (as most of the original team has changed) is the tangible result that we can feel from it. We know how many users use our server and we know that it helps put pressure on employers at a relatively low cost of effort from us. We give employees a pressure tool and they use it effectively. As far as we’re concerned, it’s a success.

Tell us a bit about how the project has changed over time.

Antijob emerged in the early 2000s as a response to the emergence of job aggregators that targeted young people, who made up a large portion of Internet users at that time. These services romanticized the “careers” they promised, and then their users learned the hard way that these careers consisted of working temporary jobs for miserable wages, followed by being firing and cheated. That was the target of our criticism; the method was formed by direct statements from employees. Over time, the Internet expanded, but the problems remained the same. The audience of job search sites increased—and so did ours.

The original version of the web page and message was more aggressive; now we are somewhat less radical. But we have not descended into orthodox Marxism, which is usually typical of groups dealing with the subject of the labor movement in Russia.

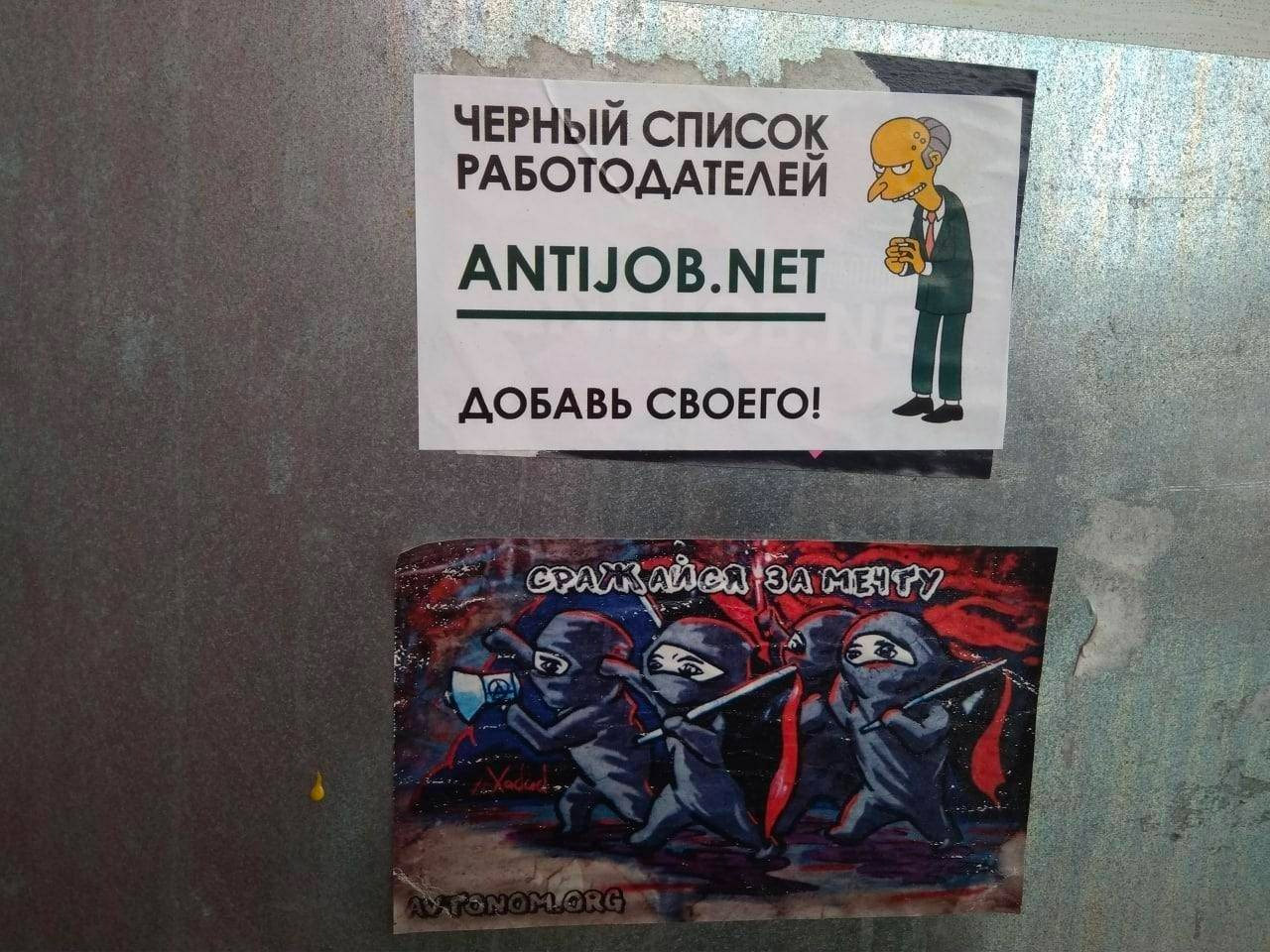

“Blacklist of employers—Antijob.net. Add yours.”

What impact has Antijob had among workers in Russia? How has the political environment changed since you got started?

You could say that our web page has been a pioneer in the field of job reviews in Russia. Employers realized that opinions on the Internet could be a threat to their businesses, and the field of “reputation work” emerged, which has itself become a kind of business.

For the authorities, we do not seem to be an obvious threat. There are lawsuits against us and the authorities even block the web site, but these problems were initiated by employers.

Of course, the situation has become worse as control over the Internet has increased. The political situation has gotten worse, too. The authorities and the police have started to write to us more often, and we are sure that sooner or later we will be blocked for good, the way it is in Belarus and Kazakhstan.

How do you moderate submissions? Do you have a fact-checking process? How do you make decisions about what you publish?

All the materials are moderated manually. We have several levels of validation; the highest level is given to those reviews in which proof of working for the company has been attached, such as correspondence or documents. Then there are reviews that are confirmed by the person leaving their email address; these are the majority.

We filter out any positive reviews because they are not objective in principle. It is almost impossible to check the validity of a positive review.

We also have an automatic review checker that alerts us to suspicious activity and allows us to identify people who are trying to misuse our web page.

We don’t do detailed fact checking. It is technically impossible with 150+ reviews coming in every week. In any case, we are not trying to claim total objectivity. For us, there is an obvious disproportion of power in the relationship between the employee and the employer—so we trust the employee more, by default.

“Labor against work.”

We understand that there have been attempts to suppress Antijob.

They often try to hack us, and from time to time, we experience brute force DDoS attacks on our web page. These attacks are organized by employers: they are either getting revenge for the reviews posted, or they are trying to remove the reviews or find out who the author is. We do not remove reviews for money, so an angry employer chooses between spending money on legal fees or hiring hackers.

The second type of attack is from what we can call “competitors” in the field of commerce. They create copies of our site, buy similar domains, and try to hijack traffic in order to make money from skimming reviews. Recently, they began to act in a more sophisticated way and attack the behavioral factors of the site using bots, which reduce the average time of visits to the site and the rate of denials in order to reduce the visibility of our site in search engines.

A separate topic is the courts and RosComNadzor (the Russian digital control authority). Some companies go to court to claim that reviews about them are slanderous. If their effort in court is successful, then after a while we get a request from RosComNadzor to remove the information. If we do not remove it, we are blocked. This has happened several times.

Now we remove reviews at the request of the RCN, attaching an invoice and a link to the court decision, which often contains the text of the review. If we do not remove the feedback, we get blocked, the website traffic decreases by 70%, and search engine rankings drop, which accordingly makes the attack on the reputation of employers less effective. We are constantly looking for ways to circumvent this threat. Recently, we managed to change it so that the blocked reviews are hidden only for Russian IPs, while all others (including VPN/TOR users) can easily view them.

Sometimes the police and other authorities write to us demanding that we provide the data of the authors. To these requests, we answer by sending the data of disposable emails and the IP of a TOR node. It is an incredible coincidence that everyone that the police are looking for is using TOR and utilizing a high level of digital security, isn’t it =). The police are not very eager to find out what’s up.

“No salary—eat the bosses.”

Can you give advice to people who might try to start something similar elsewhere?

It must be said that starting such projects from scratch can be difficult. The weapon of our web page is its high visibility in search engines and the fame it has accumulated. Those who want to start should be prepared to work for free, but at a higher level than commercial companies. The reputation market appeared long ago and there are a lot of people who want to make a profit in it and are ready to invest resources. For example, we have to contend with commercial feedback pages, competitors intercepting users by advertising, bot attacks on the web page, etc.

We are inconvenient for our competitors and for employers because of our adherence to the principle of not removing reviews for money. However, if you have a team or a powerful movement, you need comrades who have technical knowledge in web development, who understand the basics of SEO [Search Engine Optimization] and security in the Internet, as companies are quite willing to pay hackers if you do not agree to withdraw feedback.

You have to be prepared to regularly spend time on moderation and on communicating with users, as well as confrontations with the state and the courts. In the Western countries, problems with the law may be even heavier than in Russia and the CIS [Commonwealth of Independent States].

At the first stage, what is most important is not super-functionality, but publicity. In terms of distribution, stickers helped us a lot. This is a trivial method, and it often did not work well in other projects, but our stickers usually hang for a very long time. Shitty work is a very understandable problem for people of any political conviction. While the anarchist movement in Russia has been active, we have accumulated enough users from big cities thanks to stickers.

“Antijob.net—blacklist of employers.” These stickers have been essential to promoting the Antijob site as a resource.

How do you see the connection between different forms of labor resistance such as labor unions, stealing from your workplace, public pressure campaigns, etc.? Which of these tactics are viable in Russia?

For us, all methods are interconnected, and each has its pros and cons, as well as regional characteristics. Unions are a good organizational structure, but in Russia they can exist only in industries with large companies and are often overgrown with bureaucracy. Stealing is a good tactic for individual sabotage, but is not looked at well in the society and is unlikely to change the global problem of wage labor. Public pressure is effective on a big enough scale, but mobilizing people to fight thousands of small daily violations of rights involving hundreds of companies is impossible. Solidarity networks as an example of distributed pressure are good, but they require resources from regional activist groups (it is unlikely that anyone will initiate something like this in Russia except these kind of groups), and so far, we have not seen examples of such groups becoming sustainable.

All of these tactics require mobilization and a degree of political freedom, which are both lacking in Russia, perhaps apart from passive sabotage (such as refusing to work effectively) or active sabotage (stealing and intentional damage), and perhaps hacktivism as well. In our opinion, the future lies in tactics that do not fall under the scrutiny of repressive structures and cannot be clearly attacked by the bosses, but which are capable of inflicting tangible targeted damage. Sooner or later, the political situation will change and the road will open up for the other tactics.

How do you see the connections between labor resistance and other forms of political activity? Over the past 40 years, we have seen labor movements, unions, and workplace struggles grow weaker in the United States, while other fields of conflict (such as anti-police rioting) have intensified. Do you have an analysis about the ways that the terrain of labor struggles is changing and how workplace struggles can remain connected to other struggles?

We see work as a central concept that will be zealously defended on all levels, from direct attacks by the police to conceptual criticism by right-wing intellectuals. Unions have been the answer before, but the neoliberal turn has provided a broad toolkit for fighting them. Struggles against police violence, like some other mass protests, are younger and more mobile in their choice of tactics that the state does not have an effective response to yet. In addition, unfortunately, in many ways, peaceful forms of resistance do not pose a concrete threat until they develop into occupations. An organized labor movement is not just about occasional rallies, but about the state having to spend money on social programs and businesses having to shell out on decent wages and offer guarantees to workers under the constant threat of strikes. This is probably more expensive than maintaining a few riot police units.

But the labor movement is often very conservative, trade unions have their own structural problems, and new practices (like solidarity networks) have not yet become an effective instrument of struggle.

It seems only natural for us that the problem of work remains relevant. The people who suffer the most from police brutality, racism, environmental crises, and other problems are rarely businessmen. They work—officially or illegally—and they suffer the toxicity of the market system. The only question is to what extent we (who are essentially part of the same workforce) can make this agenda relevant.

In the United States, there has been a lot of news coverage of the so-called “Great Resignation,” discussing all the workers who have been quitting their jobs since the beginning of the pandemic. Has anything like this happened in Russia? Is quitting a job a form of resistance?

Russia has also had great resignations—even though these weren’t really resignations, it was more like businesses firing people to cut costs. Without benefits or any guarantees. The first lockdown made the atmosphere so tense that there were no more lockdowns afterwards. People were out of work, and since most Russians had no savings but did have credit debts, everything escalated. The state limited itself to a few cash handouts. If people were not allowed to go out to work and earn their bread, an uprising driven by hunger would have been unavoidable.

In Russia, quitting a job as resistance is relevant only for those spheres where there is a shortage of personnel and a sense of their value. Mass resignations are very unlikely because there is no broad self-organization; the resignations of a few employees do not cause any damage. People often work unofficially, so they will receive no compensation, and the benefits to the unemployed are very small. More often, a visible form of struggle will be the continuation or sabotage of work as an individual practice. We are not seeing the opportunity for mass organized action just yet.

One of several video shorts by Antijob.

Have you seen the Antiwork reddit page from the United States? How is it similar to your project, and how is it different?

Not only have we seen it, but we also have covered it, including a similar movement in China. In terms of its radical message, the movement is similar to the early Antijob, and we hope that at some point this will become more relevant in our country as well. For us, we see anti-work as a fatigue with the neoliberal work ethic (in the United States) and the pseudo-communist work ethic (in China). It seems that in our country, this ethic has not yet reached the peak after which a radical rejection of work will be perceived seriously.

Another problem with this framework is our audience. Some of them work for something like $300-400 per month, while living with children and credit debts. It would be somewhat awkward to urge them to refuse to work.

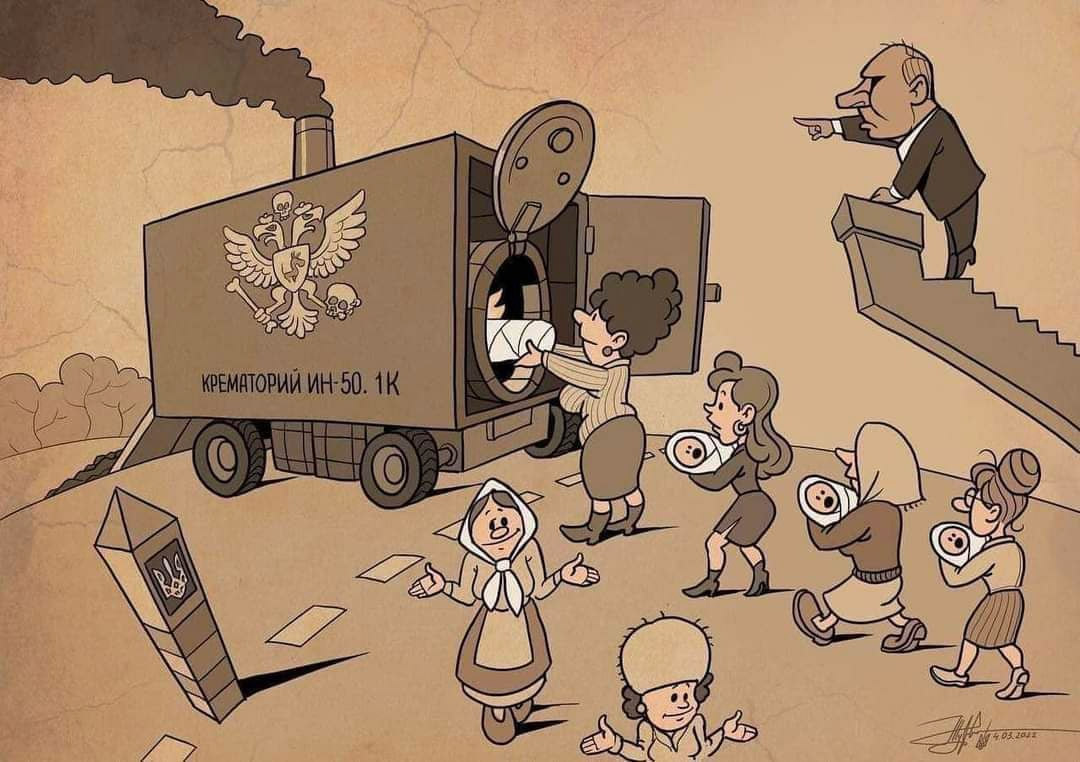

What can you say about the invasion of Ukraine from where you are positioned?

Before the war started, some of us doubted that such a turn of events was really possible. However, it did happen. We issued a statement condemning Russian aggression. Russia’s imperial policy is obvious to us. As usual, it is disguised as “security interests.” We have received several insults from patriotic users trying to prove to us that the war is being fought against “Nazis who spread LGBT propaganda,” but this is different from the patriotic frenzy of 2014 [when the Russian military seized Crimea from Ukraine].

“No salary—eat the bosses.” The sticker is in Ukrainian.

How is the invasion of Ukraine affecting Russian workers? How are the sanctions affecting workers in Russia, and how do you think they will impact the working class in Russia in the future?

There are definitely people in Russia who approve of the war, and there are quite a few of them. Many workers live in the information bubble of the state’s “fortress under siege” narrative. From their screens, they see the message “Everyone is against us.” This mobilizes them to support the invasion, shifting the focus to the idea that this is being done for the security of Russia.

Propaganda platforms use the international sanctions and condemnation to reinforce this narrative in order to draw support even among those who hesitated at first.

This mobilization will not continue indefinitely, of course. In a few months, everyone will feel the economic consequences, and if the war is lost, the reputation of the government will be damaged. This will not necessarily lead to an uprising, but we can hope that the social agenda will be more successful in mobilizing for the overthrow of the regime.

We plan to be ready for such a turn of events and, as a project directly related to labor issues, to support this process.

Finally, is there anything people can do to support your project?

The easiest way is to support us financially. The development of a project like this always needs resources with which to pay for hosting, or someone else’s work on the project. In addition to this, you can help spread awareness of the project. This is especially important in the CIS countries. Also, we always need people with experience in penetration testing to help find and fix vulnerabilities, and SEO experts to advise us on promotion in different regions in order to increase pressure on employers.

And on the macro-level, you could create an analogue of our project in your area and contact us to create a network of services like ours in collaboration.

Antijob participated in publishing this book, “‘Work Sets You Free’—Stories about Workers and Employers.”

Appendix I: Labor Resistance

This manifesto, which appeared on the Antijob site a decade ago, spells out their basic analysis and goals.

A significant part of life, we have to give work. Our capacity, time, ideas, successes and failures are reduced to rubles, dollars, and euros—empty bank notes that can never fulfill our desires and needs. Usually this work is accompanied by delays in paychecks, the machinations of employers, nervousness and humiliation from ridiculous rules and idiotic bosses.

We do not believe that the existing system of “commodity-capital” relations, which put the exploitation and destruction of people and the planet on the conveyor, can somehow be reformed “from above.” Real change can only come about if people recognize their plight and begin to seek better conditions for their lives on their own—without begging for anything from party bureaucrats or crooks from the bureaucracy.

History shows many examples of rebellious people sweeping away exploiters and thieves overnight, administering true justice and distributing public goods fairly among those who need them most. In this sense, we are closest to the libertarian (anarchist) philosophy and principles of direct action. You can read more about this in the “Library” section of our website.

We have no paid employees and no hierarchy. We focus on the use of a wide range of methods of struggle in labor conflicts. We deal with problems related to working conditions and payment, as well as problems that women, young people, and national, sexual, and religious minorities face at work.

Through our actions and propaganda, we are trying to develop class consciousness among employees and an understanding that, as a class, we have an interest in social revolution, the victory of which will offer us the opportunity to control our lives.

We see our site not only as a place where there is a black list of employers (and where you can leave feedback about employers), but also as a place for coordinating forces in the class struggle, promoting “direct action” in resolving labor conflicts—as opposed to the bureaucratic judicial system, which actually operates in the interests of our class enemies.

This site was created over sixteen years ago by several members of the organization Autonomous Action and has been actively developing all this time. This year, Solidarity Networks were created in various cities of Russia, which have already helped people to reclaim stolen wages (Novosibirsk, Irkutsk, St. Petersburg). Thanks to antijob.net, more than a dozen employees received a salary after publishing a review on the site, because many employers are afraid to be included in such lists—and even more so on our site.

“Labor against work.”

Appendix II: Antijob Statement Against the War in Ukraine (February 24, 2022)

This war is provoked by the stifled ambitions of the Russian elites. They try to disguise this by talking about the “national interest.” But the working people do not and cannot have any interests in the oppression of the people in Ukraine and the Donbas. Our interests are peace and decent work, not war with the Ukrainians.

This is military aggression initiated from the top of the Russian Federation. Yet we will be the ones who bear the consequences of this decision. The oligarchs and the president will not bear the brunt of military spending. Their children will not go to the front, their salaries will not be eaten up by inflation and currency depreciation. You and I have been set up.

The Putin regime is now taking revenge on the Ukrainian people for not wanting to live under the boot of the Russian Chekist [i.e., the Cheka, the Soviet secret police agency from 1917-1922, and its descendants, the NKVD, the KGB, and today, the FSB]. Tears and coffins await our mothers, too, but bombs will fall on the heads of our brothers and sisters, workers in Ukraine. We allowed this, but now our task is to stop it as soon as possible.

Today at 7 pm, anti-war actions will take place in Russian cities. Our antijob.net team calls on you to join them and demand an end to military aggression.

Antijob helped to publish a Russian translation of our book about capitalism, Work. Tragically, the artist who designed it took his own life this week in response to the dehumanizing experience of seeking asylum—first in Ukraine, then in Poland.

https://twitter.com/crimethinc/status/1505616538749050884

Appendix III: Worker Reviews

JSC RTK is the official retail chain of MTS. Why should it be blacklisted?

1) Management style: Feudalism with authoritarian and totalitarian methods of influence. That is: all retail is divided into divisions, regions, and sectors, at the head of each such division is a person who most often feels like the absolute ruler of the territory entrusted to him and thinks that he has the right to humiliate his subordinates, put strong psychological pressure on them, force his subordinates to deceive customers, without their consent, or assuring them that “It is mandatory” to add items to purchase receipts that: a) are very marginal, b) are absolutely useless for the client. All this is done under the fear of disciplinary action, fines, demotion, or dismissal.

2) Liability. Every month, inventories are carried out by the store and every three months—with the auditor. All employees must be present at these inventories, regardless of whether they have a work shift that day. Returning to work on the day of the inventory is paid only for those who have a scheduled shift. In case there is a shortage, the re-sorting most often does not overlap; in this case, the surplus is put on the balance, and the shortage is withheld from employees. The shortage is retained in full, and not at cost, as required by the labor code…

At work, they held a meeting at which they announced that the entire team was being transferred to minimum wage due to problems in the company… Naturally, I wrote a letter of resignation, but it turned out that none of the employees was going to quit anymore, everyone continued working as usual. While I was working for two weeks before my dismissal, I found a vacancy on hh.ru [headhunter, a popular job search site] for my own workplace, at the previous salary, and I was very surprised. Some time after my departure, the former director called me for a conversation and offered to let me return on the condition that I stop going to political pickets and covering my actions on social networks. Allegedly, there were complaints from my clients that I was against Putin. That was the reason for my removal. In fact, it turned out that no one’s salary had been reduced, everyone was quickly returned to their previous working conditions, but they decided not to inform me about this, so that I would quit of my own free will without scandal. And this whole performance was carried out in order to deceive me, one person, and force me to quit.

This surprising story was confirmed with a photograph of the contract, which is available on the post on the Antijob site.